🧵 Generics

-

Generics

- Generics in Rust provide a way to write code that can work with multiple types.

- Rust conventionally uses the letter

Tas a type parameter name, but we can use any identifier. - Rust’s type inference works well with generics, allowing you to write generic functions without specifying the type parameters.

fn print_values<T: std::fmt::Debug>(x: T, y: T) { println!("Value 1: {:?}", x); println!("Value 2: {:?}", y); } fn main() { print_values(1, 2); print_values("hello", "world"); } // Output: // Value 1: 1 // Value 2: 2 // Value 1: "hello" // Value 2: "world" -

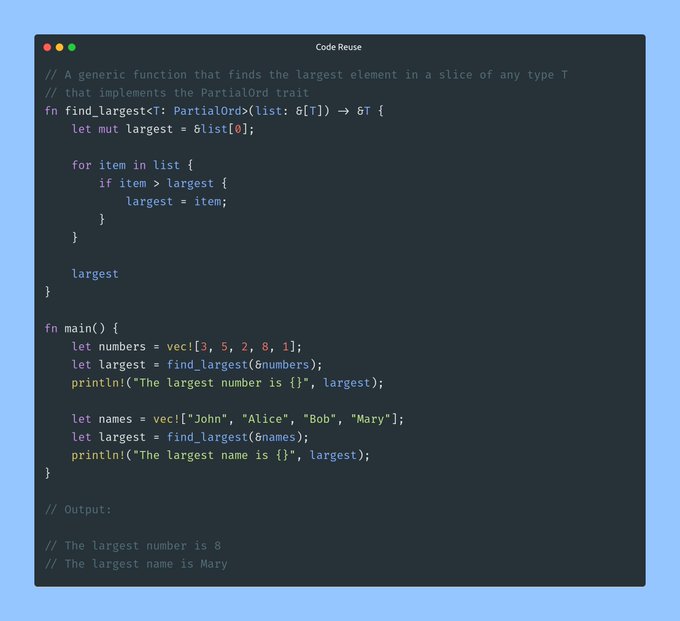

Code Reuse

- Generics in Rust also enable code reuse and make it easier to write modular and extensible code.

// A generic function that finds the largest element in a slice of any type T that implements the PartialOrd trait fn find_largest<T: PartialOrd>(list: &[T]) -> &T { let mut largest = &list[0]; for item in list { if item > largest { largest = item; } } largest } fn main() { let numbers = vec![3, 5, 2, 8, 1]; let largest = find_largest(&numbers); println!("The largest number is {}", largest); let names = vec!["John", "Alice", "Bob", "Mary"]; let largest = find_largest(&names); println!("The largest name is {}", largest); } // Output: // The largest number is 8 // The largest name is Mary -

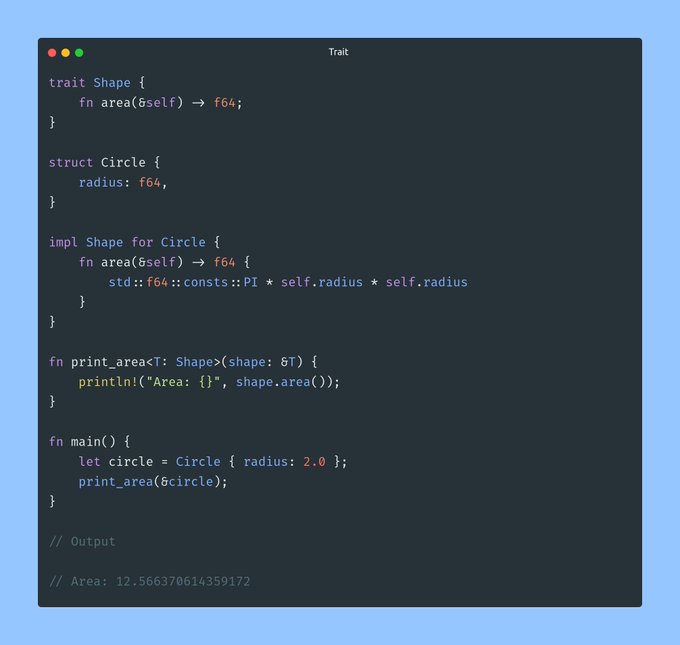

Trait

- Rust’s trait bounds allow you to specify that a generic type must implement certain traits in order to be used in a particular context.

trait Shape { fn area(&self) -> f64; } struct Circle { radius: f64, } impl Shape for Circle { fn area(&self) -> f64 { std::f64::consts::PI * self.radius * self.radius } } fn print_area<T: Shape>(shape: &T) { println!("Area: {}", shape.area()); } fn main() { let circle = Circle { radius: 2.0 }; print_area(&circle); } // Output // Area: 12.566370614359172 -

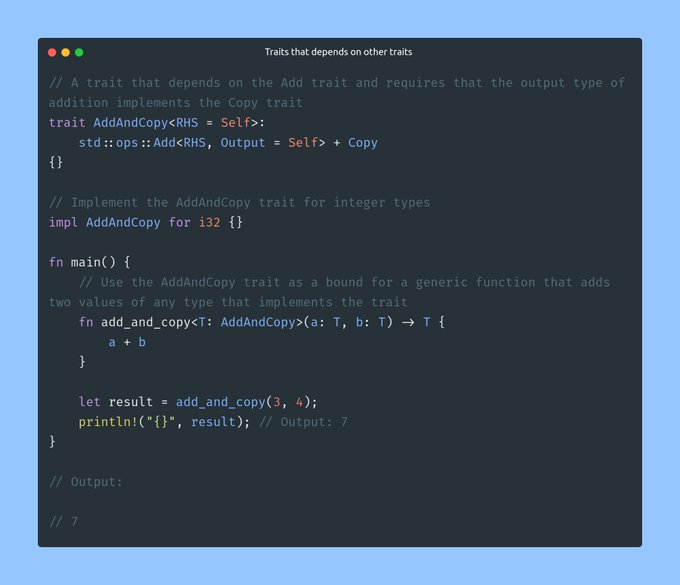

Traits that depends on other traits

- With Rust generics, you can define traits that depend on other traits. This makes it possible to express complex relationships between types.

// A trait that depends on the Add trait and requires that the output type of addition implements the Copy trait trait AddAndCopy<RHS = Self>: std::ops::Add<RHS, Output = Self> + Copy {} // Implement the AddAndCopy trait for integer types impl AddAndCopy for i32 {} fn main() { // Use the AddAndCopy trait as a bound for a generic function that adds two values of any type that implements the trait fn add_and_copy<T: AddAndCopy>(a: T, b: T) -> T { a + b } let result = add_and_copy(3, 4); println!("{}", result); // Output: 7 } // Output: // 7 -

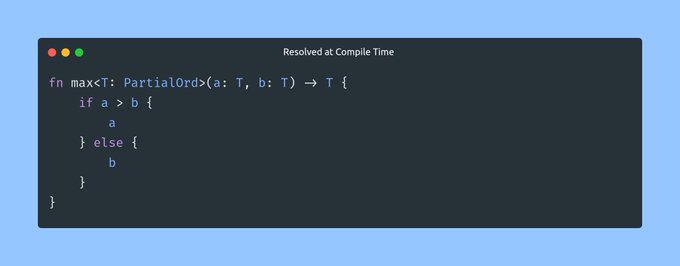

Resolved at Compile Time

- Generic types are resolved at compile time, which can result in faster and more efficient code.

- For example, consider the following

maxfunction. If we call it with twoi32values, the compiled code will only include the comparison operator fori32, which is faster than including all possible comparison operators for all possible types.

fn max<T: PartialOrd>(a: T, b: T) -> T { if a > b { a } else { b } } -

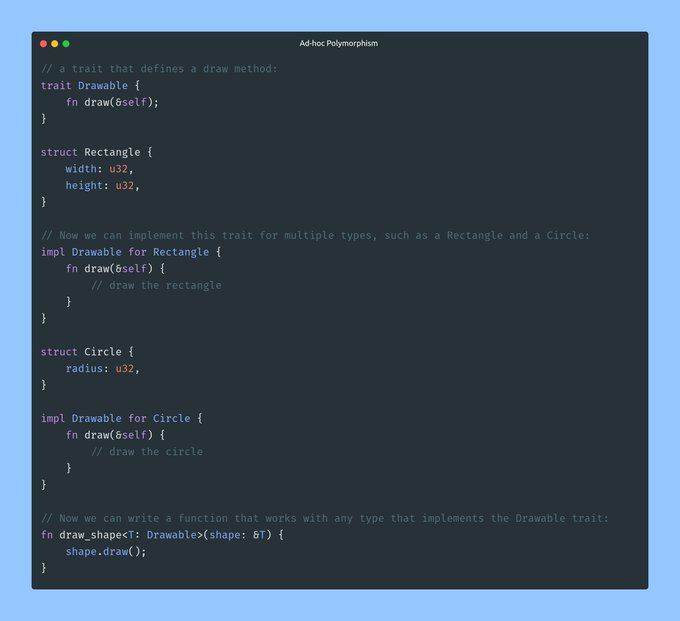

Ad-hoc Polymorphism

- Rust’s trait system allows for ad-hoc polymorphism, enabling you to write code that works with multiple types without using inheritance.

// a trait that defines a draw method: trait Drawable { fn draw(&self); } struct Rectangle { width: u32, height: u32, } // Now we can implement this trait for multiple types, such as a Rectangle and a Circle: impl Drawable for Rectangle { fn draw(&self) { // draw the rectangle } } struct Circle { radius: u32, } impl Drawable for Circle { fn draw(&self) { // draw the circle } } // Now we can write a function that works with any type that implements the Drawable trait: fn draw_shape<T: Drawable>(shape: &T) { shape.draw(); }

You can refer to this twitter thread for more info.